One of the key features of the Paris Agreement, the landmark climate deal adopted in 2015 at the end of the 21th UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP 21), is the recognition that increased efforts to cope with the impacts of climate change are strongly needed. By establishing a long-term adaptation goal, the Paris Agreement, for the first time in the history of climate change negotiations, elevates adaptation at the same level of mitigation. More broadly, the Agreement implies the urgency of undertaking an integrated perspective, going beyond stand-alone emission reduction strategies, to foster a climate resilient and inclusive low-carbon development.

This has a crucial relevance in terms of climate change policy. Indeed, even in the – unlikely – case the mitigation goal of keeping global average temperature increase below 2 or even 1.5°C will be achieved, some climate change impacts will inevitably be experienced. Climate related negative effects are, however, projected to impact primarily developing countries that are not only expected to confront with major climate change impacts but often have a reduced capacity to face them adequately. Moreover, adaptation plans need to be considered in the wider context of economic growth and poverty eradication priorities of these countries.

In identifying what adaptation looks like on the ground, the research community agrees on the fact that socio-economic development represents, in many instances, the foremost strategy to reduce vulnerability As a key enabling component of development, energy therefore plays a crucial role also in adapting to climate change impacts. A look at the literature on energy services may help to clarify the linkages between energy uses and adaptation. Of the list of energy services provided by Fell (2017), for example, some are clearly climate sensitive. Among them, space heating and cooling allow households to maintain the desired levels of thermal comfort in their living environment, thus alleviating climate-related damages to health. Similarly, cooling systems make commercial and industrial activities possible in places where already difficult climatic conditions can negatively influence production levels and labour productivity. Another example is the increased demand for water as a consequence of extreme droughts, which implies greater dependency on energy in both the agricultural and residential sectors. According to this approach, energy use for adaptation can be defined as those functions and actions that use energy and reduce the vulnerability and exposure to climate change. On closer inspection, large part of the above-mentioned energy services crucially overlaps with the basic energy requirements necessary to ensure minimum standards of decent living, thus reinforcing the mutual synergies between universal energy access objectives and adaptation. However, tensions can potentially arise when additional energy demand due to increased adaptation needs conflicts with the objective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels consumption.

The Paris Agreement offers the opportunity to better understand which adaptation options involve a significant use of energy and how they are going to be implemented practically. Through their bottom up approach, the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) represent, indeed, a powerful tool revealing countries’ preferences and interests about present and future climate change action. Among the more than 190 national governments that submitted a NDC to the UNFCCC, about 140 include adaptation plans, proposed especially by emerging and developing countries, whose priority in protecting their people from dangerous climate impacts is more urgent. NDC can therefore help in shedding light on whether and how countries perceive energy to be a critical factor for adaptation.

Small Island States seem particularly aware of the issue, with Antigua and Barbuda proposing on top of their objectives to increase, by 2025, their seawater desalination capacity by 50%. According to the country’s NDC, adaptation in the water sector is of national priority. Desalination in particular, regularly provides already 60% of domestic freshwater supply, which increases to 90% in time of drought.However, with the majority of desalination plants powered by fossil fuels, desalination process is the most energy intensive water treatment method. But water is crucial also for agriculture and food security. Many among less developed countries, including Malawi, Zambia and Lebanon plan to increase the use of irrigation methods and/or the land area under irrigation. Beyond the issue of the efficiency of the different systems, this would translate into increased use of both water and energy. Data show that already 56% of global irrigated land requires energy, and the figure is expected to grow either because farmers gain access to modern energy for pumping and because of increasingly unpredictable, insufficient rainfall. Among the adaptation challenges in the residential sector, Lebanon explicitly recognizes the need for the national electricity infrastructure to deal with the augmented demand for cooling as air temperature will increase. On the contrary, Uruguay climate strategy aims at addressing both mitigation and adaptation through the implementation of energy-efficiency labeling in household devices such as air conditioners and refrigerators.

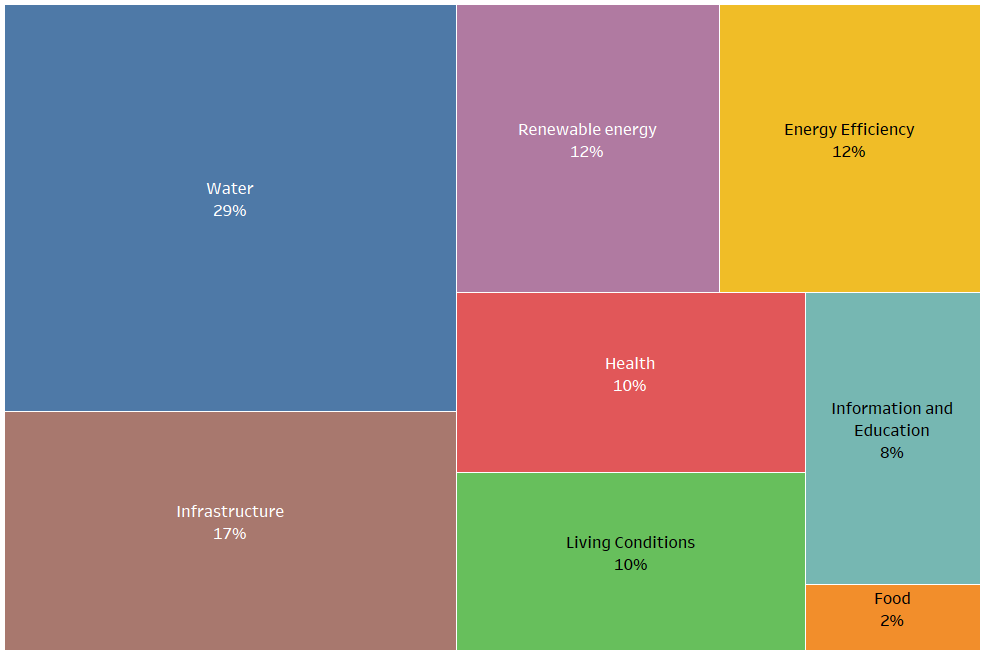

From a preliminary analysis of climate change priorities included in developing countries’ NDCs, energy use for adaptation emerges as a key issue, involving all major sectors of the economy. Overall, about one third of total energy for adaptation measures identified are related to the water supply sector, followed by the infrastructure, which includes the provision of basic public services like electricity, buildings and transport. Also, energy efficiency technologies and renewable energy sources, accounting each for 12% of total options, are going to play a critical role as key solutions bridging mitigation and adaptation need.

Crucially, the health services are often mentioned (10%) as a sector that urgently needs to be extended and improved to adequately respond to extreme whether events and potential climate change implications for human wellbeing. Enhanced information and education, which are typically considered as behavioral adaptation strategies but rely on energy access to reach the most vulnerable communities and spread their effect, represent 8% of total identified measures. A smaller but not insignificant shares of adaptation actions are linked to the energy uses aimed at ensuring decent life and working conditions as well as to the protection of vulnerable livestock and the adaptation of food infrastructure.

Looking carefully at single examples, the NDCs also show that some countries are aware of the potential trade-offs between mitigation and adaptation, as they propose renewable-based options to reduce the carbon emissions of high energy intensive adaptation actions. In some cases, however, the picture is less clear, with the final impact depending on the type of technologies and efficiency levels countries will actually choose to put in practice their adaptation plans.